Nancy Pontius is ready to share an unpopular view: she doesn’t think inflation is a major issue, and says concerns about the economy won’t influence her vote in November’s election.

But that’s not because the 36-year-old Democrat hasn’t felt the same financial strain as tens of millions of Americans over the past couple of years.

“I definitely felt the gas price increase,” the mum-of-two from Pennsylvania says, “but I also recognised that it was likely to be temporary”. Ms Pontius voted for Joe Biden four years ago and plans to do so again, motivated by issues like abortion. “I’m not worried about the big picture economy,” she says.

Such confidence is welcome news for Mr Biden, whose first term has been troubled by a once-in-a-generation 18% leap in prices, which propelled economic dissatisfaction and eroded political support.

Even as the American economy’s booming emergence from the pandemic drew envy abroad, opinions at home remained starkly negative.

Now there are signs that may be changing, as petrol prices fall back towards $3 a gallon nationally and wages get closer to catching up with price rises.

Economic sentiment – what some pollsters describe as the “vibe” that people feel around the economy – has improved in business surveys in recent months.

Democrats like Nancy are now as positive about the economy as they were in 2021, when prices had just started their climb – and more positive than at any point during the Trump presidency, according to the University of Michigan, which has surveyed consumers for decades. Even the views of Republican voters have brightened a bit, their research indicates.

The White House hopes the change in mood will last and shore up support for the president as the election approaches in November – especially in crucial swing states like Pennsylvania.

But that’s far from guaranteed.

The president’s approval ratings are hovering around the lowest levels of his term, hit by concerns over immigration, his age and the war in Gaza.

And despite the positive signs, overall economic sentiment has yet to recover from the beating it took during the pandemic, despite solid growth and a historic streak of unemployment below 4%.

Among Democrats, the issue is particularly hurting Mr Biden with those under the age of 30, just a quarter of whom rated the economy as excellent or good in a recent Pew survey, compared to 70% over the age of 65.

Kim Schwartz, a 28-year-old health technician from Pennsylvania, voted for Mr Biden in 2020 but has been disappointed by his economic policies.

“I don’t see any progress in getting more money into the hands of middle class and working class Americans to keep up with [inflation],” she says.”I am going to vote, but whether it will be a write-in or third party or Biden, I don’t know.”

Though her financial position has improved since 2020, when she was struggling to cover her expenses while studying and working part-time, she still scouts multiple grocery stores each week in search of the lowest prices.

She has deferred work on her car due to cost concerns; and big financial and life goals, like buying a house, still feel achingly out of reach.

“I am surviving,” she says. “It’s enough to maintain but it’s not enough to improve or progress.”

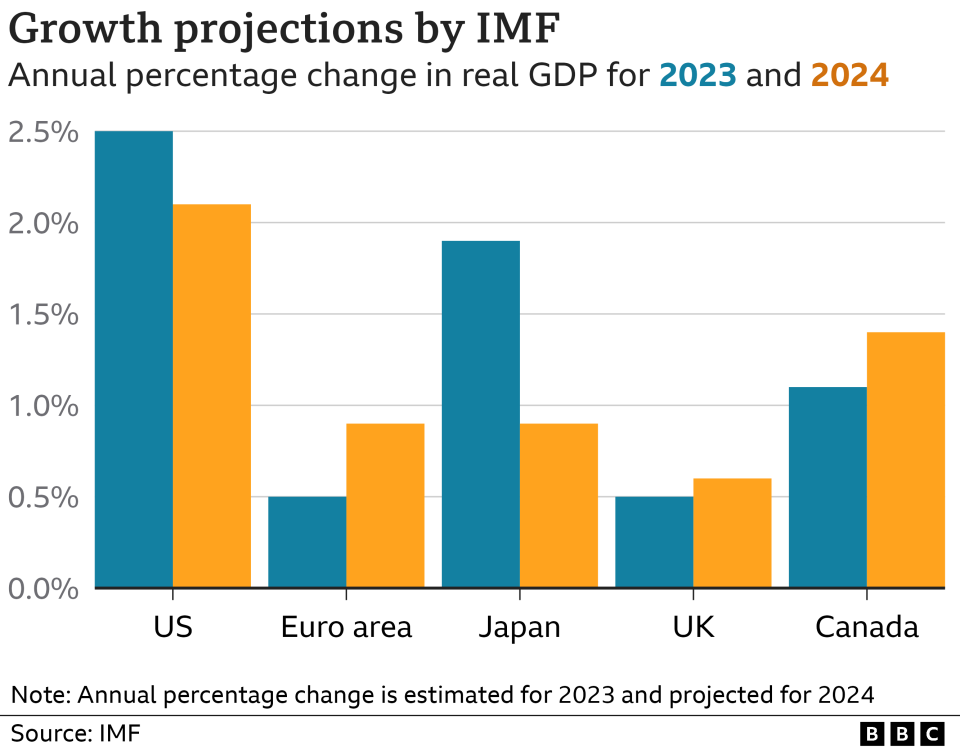

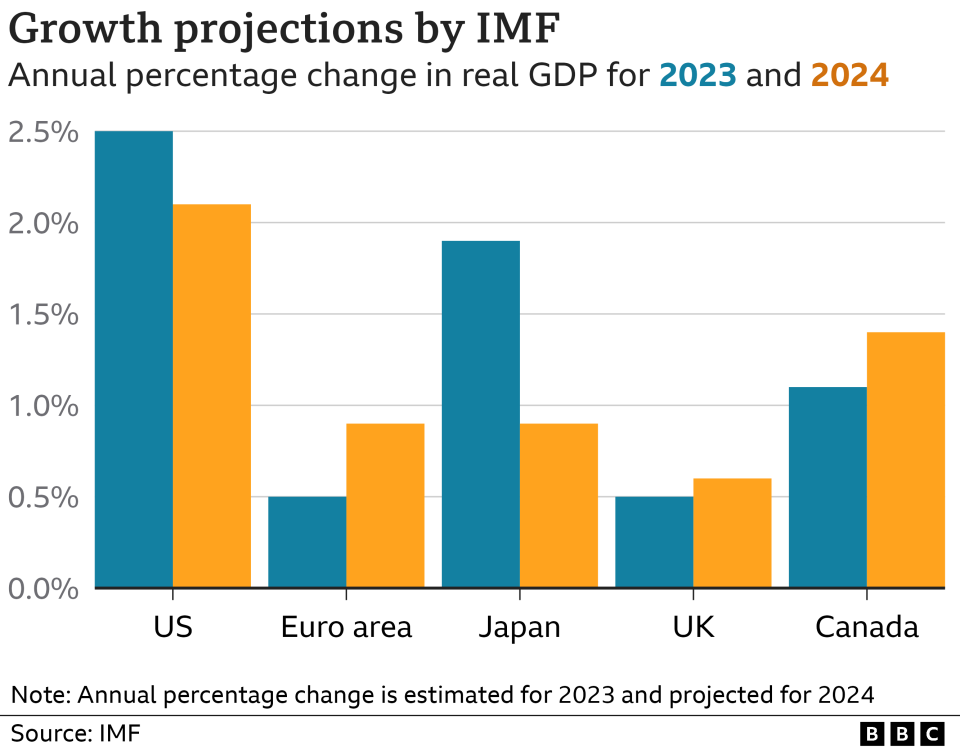

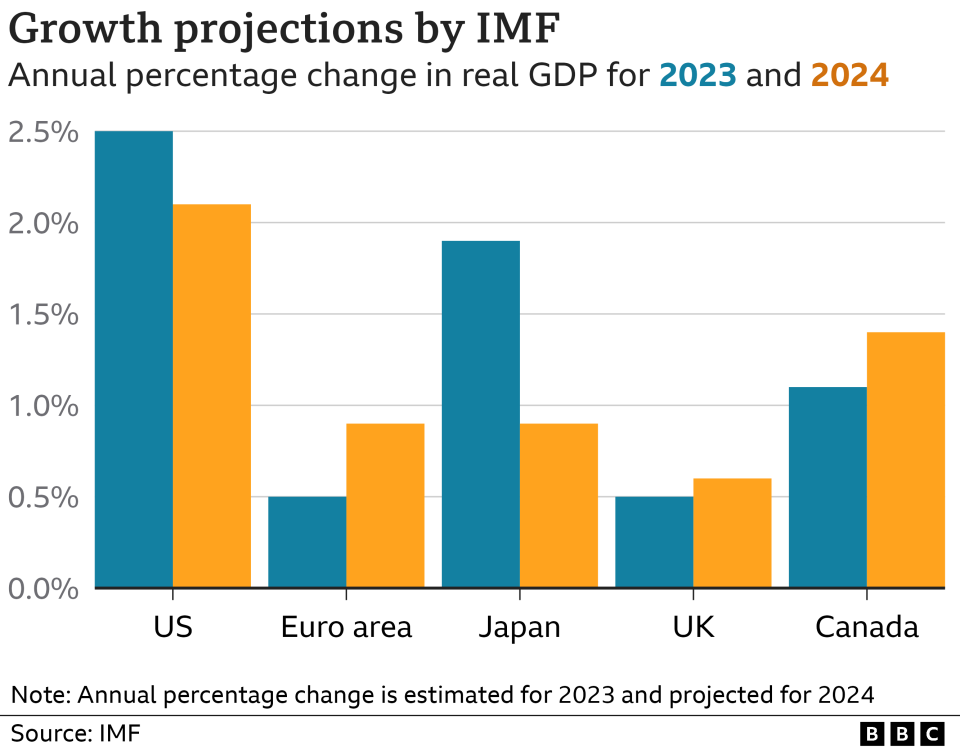

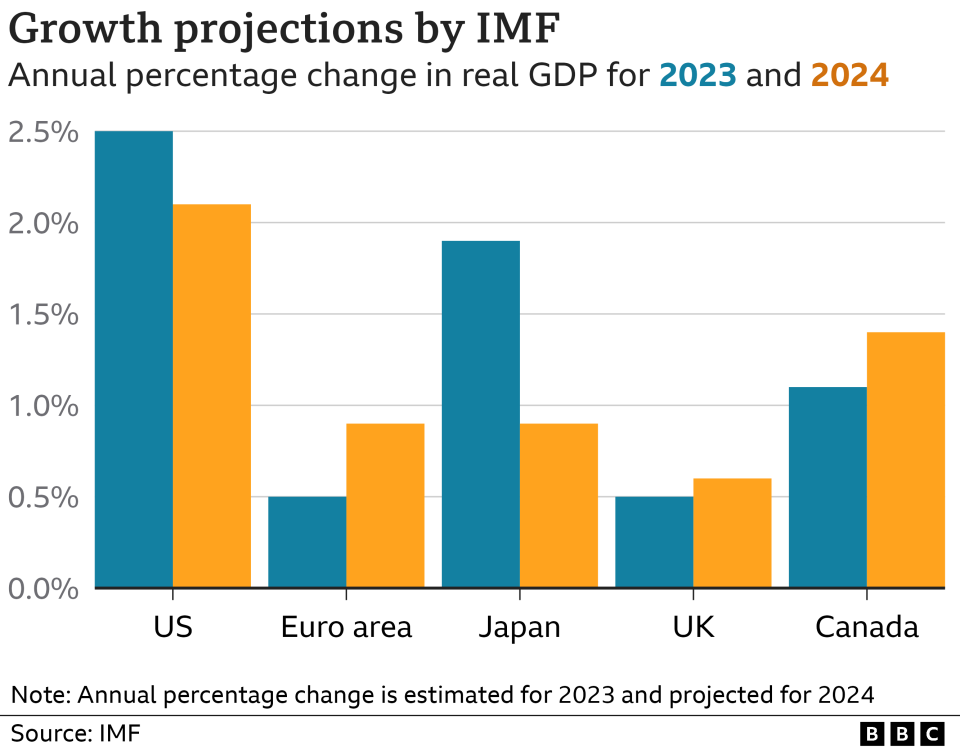

It’s a truism of American politics that the state of the economy decides elections. On that basis, Mr Biden should be in safe territory, with growth of 2.5% last year and inflation down sharply from its 2022 high, at 3.1% last month.

But the typical weekly wage in the US, adjusted for inflation, at the end of last year remained lower than it was when Mr Biden took office.

Frustrations like Kim’s turn up repeatedly in political polling, where majorities express serious concern with the price of food, consumer goods and housing and describe the state of the economy as “poor” or “fair”.

“It’s like a race and you’re trying to keep up with it,” says John Cooke, a 34-year-old restaurant manager in Pennsylvania.

Though business at the eateries where he works has been good, he says inflation has cut into profits and he has not had a pay raise.

“Car insurance has gone up, health insurance has gone up, my rent has gone up. They are saying the economy is doing great. That’s great to show me all these numbers but how is that helping me?”

Republicans, who have an historic advantage among voters on economic issues, have made the economy one of their key lines of attack, hammering Mr Biden on inflation and blaming his “tax-and-spend” agenda for driving up prices.

Economists say generous government financial support for households during the pandemic did help to fuel inflation by lifting consumer demand and cushioning household budgets, allowing firms to put up prices without major blowback.

But the shock to oil prices from the war in Ukraine and supply shortages tied to the pandemic also played important roles.

Democrats have held their own in elections since 2020 – including the 2022 midterms – by blaming wider forces for inflation and focusing on non-economic issues that motivate the base. But independent and infrequent voters, for whom the economy ranks highly, are more likely to vote in presidential contests.

“The core issues the Biden coalition cares about are still issues like abortion, like gun safety, like voting rights, like climate change,” says Danielle Deiseroth, executive director at the progressive pollster Data for Progress. “But in an election that’s going to come down to a couple thousand votes in a couple of states, you can’t leave any issue off the table for swing voters.”

Strategists say Mr Biden for too long relied on the big national numbers to defend his record – a response that felt emotionally out of touch.

“When you just say the economy is great; GDP is great – nobody ever bought a dozen eggs with GDP. Nobody cares,” says pollster Celinda Lake, who worked on Mr Biden’s 2020 campaign.

That criticism appears to have landed. In recent weeks, Mr Biden has adopted a markedly more populist tone, attacking companies for price gouging and “shrinkflation” – charging more for less – and sharpening his criticism of “extreme MAGA Republican” economic policies.

Don Cunningham, a long-time Democratic politician in Pennsylvania, says he expects the disconnect between economic sentiment and reality to heal in the months ahead.

Mr Cunningham leads the Lehigh Valley Economic Development Corporation – drumming up investment in a former steel-making region that was hit hard in the 1980s as the industry hollowed out, but is enjoying a revival today.

“I see challenges [for Biden] there but they are not related to economic issues,” he says. “How people are feeling personally, how candidates make them feel, if there’s an age gap, if younger folks are frustrated because there’s not someone from their generation… those are all real issues that go into how people vote and why people vote.”

There are signs a significant number of Americans are dismayed by the likely choice they face in November – with Mr Biden and Mr Trump looking set for a 2020 rematch.

Even Nancy’s urgency has cooled. Four years ago, she proudly planted a Biden sign on her lawn, but going into the 2024 race she’s planning to take a lower profile, leery of alienating her neighbours.

“We might still put the Biden-Harris sign out,” she says. “But I was willing to be a little louder in 2020… than I am now.”

If you’re in the UK, sign up here.

And if you’re anywhere else, sign up here.