Congress appears unlikely to pass any of the laws it has been promising to safeguard this year’s election from the threat of artificial intelligence.

With experts warning about threats to democracy from AI deepfakes that mislead voters, lawmakers said they had to act — and they introduced multiple bills this year that could have banned deepfakes in elections and mandated clear labels on AI-generated content. Despite the appetite for laws and some bipartisan support, those efforts are foundering.

But interviews with lawmakers and Hill staff and a reading of fall’s brief remaining legislative schedule suggest that time has already run out for what was supposed to be a top priority — protecting elections from a powerful tool of deception.

“I would certainly love to see something on the floor. But I’m not sure that we’re going to,” said Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.), one of four members of a bipartisan Senate group chosen by Democratic Majority Leader Chuck Schumer to work on AI last year.

It’s a dramatic comedown from when the Senate first began grappling with generative AI last year, dedicating a full closed-door meeting with experts to the threat AI posed to elections. Speaking at the end of that session last November, Schumer warned that the coming vote would be “the first national elections with widely available AI technologies that can accelerate the spread of mis- and disinformation, so we must act quickly.”

Republican Sen. Todd Young of Indiana, part of Schumer’s handpicked, bipartisan team to shepherd AI laws through the Senate, told POLITICO in January that AI in elections was “probably going to be one of the most important items that we look at as early as possible.”

Schumer did not confirm whether the leading bills to regulate AI-generated election content are toast this Congress, but in an emailed statement he hinted he had extended his timeline.

“Efforts to address AI in elections can and must continue beyond the 2024 election,” Schumer wrote POLITICO in response to questions for this story.

Young and his fellow Republican in Schumer’s AI group, Sen. Mike Rounds of South Dakota, did not immediately respond to questions on AI and elections.

Republicans have already blocked Senate bills to regulate voter-facing AI-generated content, with no indication that anything will change before Nov. 5. The House is even further behind, with a planned report containing legislative recommendations on a number of AI issues — including the use of generative AI in elections — yet to be released.

For the remaining weeks of the 2024 campaign, that means the only safeguards against deepfakes in elections are in states that passed their own laws, and in federal agencies that have stepped in — though they are hamstrung by the limits of their power and internal partisan fights.

“We’ve seen deepfakes be decisive in elections around the world,” argued Robert Weissman, co-president of the nonprofit advocacy group Public Citizen. “It is irresponsible to act as if it cannot happen.”

Americans first reckoned with the malicious use of generative AI in elections back in February when deepfaked robocalls impersonating the voice of President Joe Biden targeted New Hampshire voters, telling them not to vote in the state primary.

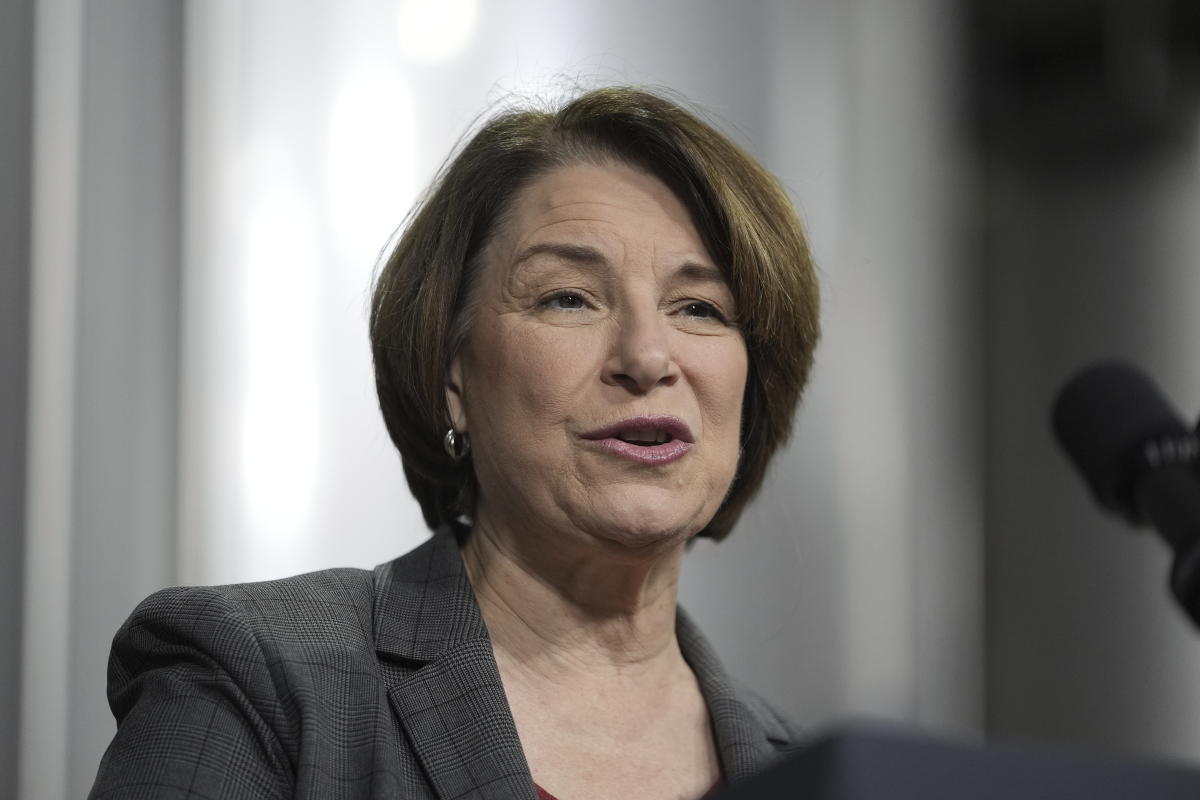

By May, Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) had introduced a trio of bills for markup. One would prepare election administrators for AI. Another would ban deepfakes of federal political candidates, and a third would require disclosures on AI-manipulated political ads.

The Senate Rules Committee advanced all three in May, despite Republican fears of hampering technical innovation and free speech. But the two bills about voter-facing AI-generated content failed to pass a unanimous consent Senate vote in July. Rules Committee ranking member Sen. Deb Fischer (R-Neb.), whose objection tanked the unanimous consent vote, did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

In a statement to POLITICO in late August, Klobuchar wrote, “As I said on the Senate floor in July, this is a hair-on-fire moment and we must take action.” Still, she appeared to be making contingency plans. An aide wrote, “Senator Klobuchar plans to ask for unanimous consent again. And if the legislation doesn’t pass as a standalone bill or part of a package, she will introduce it in the next Congress.”

Klobuchar’s bills were the highest profile on AI in elections and gathered support from Republicans including Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri, Maine’s Susan Collins and Alaska’s Lisa Murkowski. None of them responded immediately to requests for comment.

In the House, work on AI has stalled even further behind. Bipartisan House leadership launched a task force in February. The task force has been meeting regularly to discuss legislative proposals on AI but has yet to recommend any laws for passage. The task force’s assigned deliverable — a report that will guide the House’s actions on AI — is still in the drafting process with no set release date. Task force Chair Rep. Jay Obernolte (R-Calif.) and Ted Lieu (D-Calif.) did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Given the state of the proposals and the pace of lawmaking in Washington, “It’s not realistic to expect action” before elections, said Minnesota’s Democratic state Secretary Steve Simon, who has watched Congress closely as his state passed its own law in 2023 to criminalize deepfakes in elections and updated it the following year to remove candidates from running or from office if they are found guilty of using deepfakes in elections.

Eighteen other states have passed laws to limit deepfakes in elections, according to Public Citizen’s tracker. Weissman said the laws are no substitute for federal law, but they do indicate an appetite for action.

“The clock is running out, and what should be a common sense consensus issue has been tarnished by reflexive partisanship,” he said.

In the meantime, agencies have used their powers to prosecute the misuse of AI, using existing rules.

Following the New Hampshire robocalls, the Federal Communications Commission issued a cease-and-desist order to the Texas telecom company that carried the calls on its network. The agency later proposed a $2 million fine against Lingo Telecom (which later settled for $1 million) and a $6 million fine against 55-year-old Steven Kramer of New Orleans for using call-spoofing technology.

Though FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel has said she wants to write new rules to regulate AI in campaign materials airing on TV and radio, efforts there are hitting the same Washington calendar. She published a proposal in July, and the FCC will be collecting public comment on the rules through nearly mid-October. It is highly unlikely the commission will vote on finalizing a rule before Election Day, and almost impossible the rule would take effect before the vote.

There has been a bit of jostling between the FCC and the Federal Elections Commission, where the Republican chair, Sean Cooksey, has insisted that only his agency has authority to enforce election law. Writing to Rosenworcel about her proposals, he said, “I believe these would invade the FEC’s jurisdiction.” Cooksey laid out his own view of the FEC’s role in an August op-ed titled “The FEC Has No Business Regulating AI.”

The FEC’s Democratic vice chair, Ellen Weintraub, told POLITICO she saw little possibility that her Republican-controlled panel would issue new rules on AI in elections. At best, she said the FEC could potentially rule on individual cases of election fraud.

John Hendel contributed to this report.